Climate change is one of the most significant challenges facing our world today and presents the single biggest threat to sustainable development everywhere. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by all United Nations (UN) member states in 2015, provide a comprehensive framework to address these challenges and promote a sustainable future for all. Among these goals, Goal 13: Climate Action is crucial in the fight against climate change.

The SDGs have faced significant criticism because numerous programs have fallen off track. The SDGs Report 2024 showed that only 17 per cent of the SDG targets are currently on track, with nearly half showing minimal or moderate progress and over one-third stalled or regressing.

Some critics pointed out that the goals are too broad and ambitious, making it difficult to focus on specific, actionable goals and leading to inefficiencies in efforts and resources. Other critics emphasise trade-offs and conflicts between different SDGs. For instance, aiming for at least 7 percent annual GDP growth in the least developed countries (SDG 8.1) might hinder progress on climate action (SDG 13) due to increased industrialisation and pollution. Some radical critiques highlight the close alignment between the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and corporate capitalism or neoliberalism, suggesting that these frameworks may prioritise profit over authentic sustainable development.

In this post, I focus on one key issue: how climate partnerships between the Global North (wealthier countries) and the Global South (poorer and developing countries) are often unequal. SDG 17 encourages global partnerships, including those focused on climate action, but many of these partnerships are unbalanced.

One problem is that countries from the Global South are often underrepresented in international climate negotiations and decision-making processes. Important decisions are made in forums like the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), where richer countries often have large, well-prepared teams. These delegations are usually English-speaking, have legal and scientific experts, and can send the same people to each meeting. Many Global South countries do not have the resources to build such teams, which limits their influence and leads to unfair outcomes. In response, they often have to come up with creative ways to make their voices heard, but the system still favours wealthier nations.

Partnerships between the Global North and South in addressing climate change are often shaped by a combination of genuine environmental concerns and strategic interests. Among the underlying motives are economic considerations: Northern countries may aim to secure access to resources and emerging markets in the Global South. Supporting climate initiatives can serve not only environmental goals but also the cultivation of goodwill and the strengthening of economic relationships.

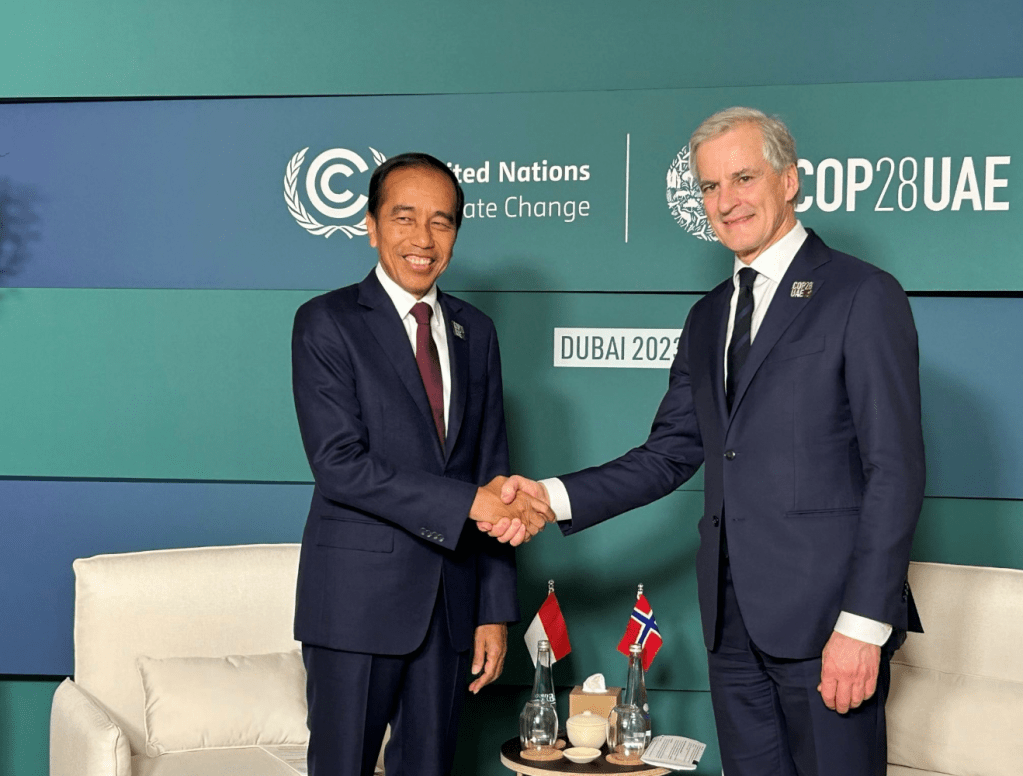

Some critics mentioned that the partnership was a new form of colonialism and a neoliberal environmental approach. For example, the Indonesia-Norway REDD+ project mitigates climate change by halting deforestation, considering the important role of absorbing and storing carbon dioxide. Svarstad and Benjaminsen argued that the partnership is a new form of colonialism that allows Norway to continue its dependence on oil while pushing carbon emission reduction to others. Alled William, in his book The Politics of Deforestation and REDD+ in Indonesia, viewed REDD+ as a neoliberal environmental approach to the global climate crisis. Norway is one of four major OECD oil producers that use oil wealth generated in one country to pay for carbon emission reduction from deforestation in another. He added that the partnership can be cast as a form of neocolonialism that uses economic and political pressure to control and influence another poorer country.

Both parties seem to be using climate partnerships to enhance their economies. Looking at the trading data between Indonesia and Norway, Norway’s top export products to Indonesia were mineral fuels, oils, and distillation products, with a total value of US$108.5 million in 2022. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s top export to Norway was nickel, with a total value of US$61.87 million during 2022. Nickel mining in Indonesia has become a significant driver of deforestation and biodiversity loss as well as an indicated violation of human rights. The partnership for climate action is just a facade masking the underlying economic interests and exploitation.

In conclusion, if we want climate partnerships to work, we need to address these imbalances. Partnerships between the Global North and South must be based on fairness, inclusion, and shared responsibility. Real climate action should respect human rights, ensure equal participation, and focus on long-term sustainability, not just short-term profits. Only then can we truly achieve the SDGs and make progress in the fight against climate change. (Meta Mulyani)