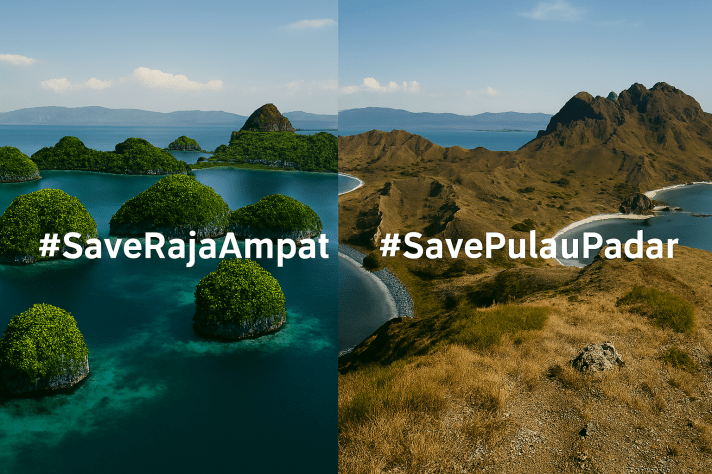

From #SaveRajaAmpat to #SavePulauPadar

Month after month, year after year, Indonesia’s netizens find themselves fighting to protect their own “heaven on earth”. Not long ago, the hashtag #SaveRajaAmpat went viral. Raja Ampat, located in the eastern province of Papua, is renowned for its pristine natural beauty, blue waters, untouched coral reefs, and hundreds of small islands. But even this ecological treasure isn’t safe. The culprit? Nickel mining, specifically on Gag Island.

Nickel has become a highly sought-after resource, particularly with the rapid growth of electric vehicles. The world’s push for green energy, while well-intentioned, has ironically fuelled environmentally destructive practices in the Global South. Countries in the Global North enjoy sleek, battery-powered cars, often unaware or uninterested that the nickel powering their green lifestyle is extracted at the cost of ecosystems and communities thousands of miles away. As someone from Indonesia currently living in a country that prides itself on green innovation, I feel a deep sense of unease knowing Indonesia pays the price for that convenience.

Today, a new hashtag popped up on my Instagram feed: #SavePulauPadar.

Pulau Padar is situated between the Komodo and Rinca islands, within the Komodo National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site. This region is globally celebrated for its stunning landscapes and, of course, its legendary Komodo dragons. But now, Pulau Padar is under threat. The Indonesian government has granted a 274-hectare concession to a company called PT Komodo Wildlife Ecotourism (KWE), which plans to build a staggering 619 structures, including 448 swimming pools, 15 cafés, 7 spa facilities, and various other developments.

For whom is this “eco-tourism” development intended? Mostly, the wealthy, especially international tourists from the Global North. These projects often cater to global luxury standards, offering the comforts of home in an exotic setting, all while displacing the very communities that call these islands home. Indigenous people whose lifestyles and needs are often disregarded now face the possibility of forced relocation in favour of luxury resorts.

It begs the question: why must international tourists and rich people expect their own standards of living wherever they go? Isn’t the essence of travel rooted in experiencing different cultures, ways of life, and environments? Why can’t they adapt to the local standard?

Unfortunately, this is a pattern we have seen time and time again. In our relentless pursuit of “development”, we equate progress with imitation, copying the lifestyles, infrastructures, and economies of wealthier nations. But at what cost? When we build for others while displacing our own people, when we destroy what makes a place special to make it more palatable, are we really developing or just giving up what matters most?

Development must be redefined.

It should not mean sacrificing local identity for international approval, nor should it mean choosing short-term profit over long-term sustainability. True development uplifts communities, preserves nature, and respects the balance between people and place. (Meta Mulyani)